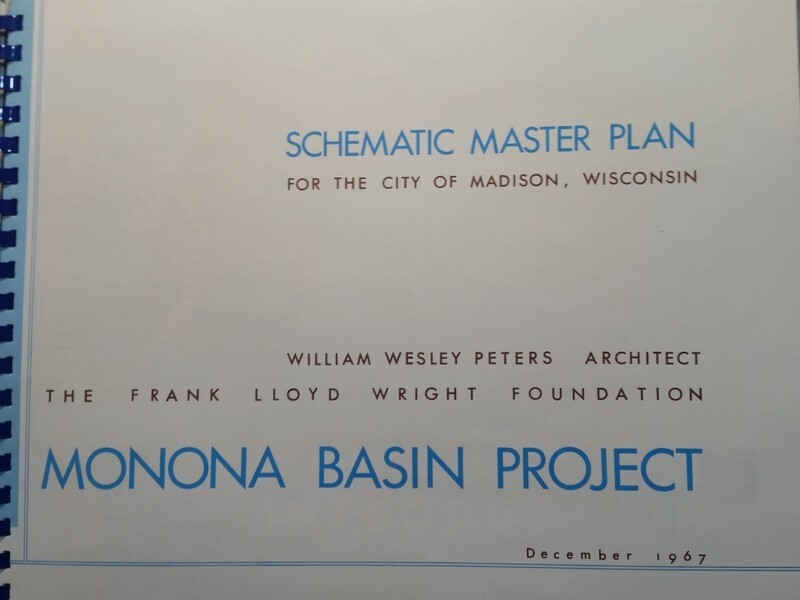

Monona Basin Project: Schematic Master Plan

Historical Context

The Monona Basin Project represents one of the most ambitious urban planning initiatives in Madison's history, with roots tracing back to Frank Lloyd Wright's original 1938 vision for the city's waterfront. This 1967 publication by William Wesley Peters documents a comprehensive master plan that sought to create a harmonious connection between Madison's Capitol Square and the shores of Lake Monona.

Frank Lloyd Wright first proposed his revolutionary plan for the Monona Basin area in 1938, funded by a local businessman who believed in Wright's transformative vision. The project was controversial from its inception, challenging conventional urban planning approaches with Wright's organic architecture principles applied to city-scale development.

William Wesley Peters: Wright's Successor

William Wesley Peters was uniquely positioned to continue Wright's vision. As Wright's son-in-law and one of his most trusted apprentices, Peters served as vice president of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation and was instrumental in preserving and developing Wright's architectural legacy after the master's death in 1959.

Peters' 1967 master plan represented what historians call a "second pass" at Wright's original concept—a refined and updated version that came remarkably close to actual implementation. The plan demonstrated how Wright's principles of organic architecture could be applied to comprehensive urban planning, creating spaces that harmonized with the natural landscape while serving modern urban needs.

The Plan's Vision

The Monona Basin Project was far more than a simple building proposal—it was a comprehensive reimagining of Madison's relationship with its natural setting. The plan included:

- Convention Center and Civic Auditorium: A major cultural and business hub that would anchor the development

- Integrated Transportation Systems: Innovative approaches to connecting different parts of the city

- Public Spaces and Parks: Green areas that would create a seamless transition between urban and natural environments

- Mixed-Use Development: Residential and commercial spaces designed to create a vibrant, livable community

- Mechanical Services Integration: Infrastructure planning that was ahead of its time

Legacy and Impact

While the complete Monona Basin Project was never realized as envisioned, its influence on Madison's development cannot be overstated. Elements of the plan eventually found expression in Monona Terrace, the convention center completed in 1997 that was based on Wright's original 1938 design concepts.

The 1967 publication serves as a crucial historical document, showing how Wright's ideas evolved through his apprentices and the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. It represents one of the few major Wright urban planning concepts to influence actual city development, demonstrating the ongoing relevance of organic architecture principles in urban planning.

Connection to Frank Lloyd Wright's Philosophy

The Monona Basin Project embodied Wright's core belief that architecture should work in harmony with its natural environment. The plan sought to create what Wright called "organic architecture" on an urban scale—development that would enhance rather than dominate the natural beauty of Madison's isthmus setting between two lakes.

This philosophy extended beyond mere aesthetics to encompass Wright's vision of democratic architecture—spaces designed to serve all citizens and create a more harmonious relationship between human habitation and the natural world. The project represented Wright's belief that good design could improve not just individual buildings, but entire communities.

Rarity and Significance

Original copies of the 1967 Monona Basin Project publication are quite rare, making this document a valuable piece of architectural history. The publication was "printed for distribution as a public information service of the City of Madison," indicating the serious consideration the plan received from city officials.

The large format document contains detailed maps, space diagrams, transportation plans, and mechanical services layouts that provide insight into the comprehensive nature of Peters' vision. It represents an important example of how Wright's ideas continued to influence American urban planning through the work of his apprentices and the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation.

Place in the Collection

This document represents a crucial link in the chain of Frank Lloyd Wright's influence on American design and urban planning. It shows how Wright's vision extended beyond individual buildings to encompass entire communities, and how his apprentices carried forward his principles after his death.

The Monona Basin Project publication complements the other Wright-related artifacts in this collection by demonstrating the practical application of his design philosophy at the largest scale. It connects Wright's educational influences (represented by the Froebel blocks), his personal artistic development (shown in his autobiography), and his appreciation for other cultures (evidenced by his Japanese print collection) to his ultimate vision for how human communities should be designed and built.